The Missing Foundation of the Reformed Doctrine of Gender

The Image of God: Weighed and Found Wanting

In How God Sees Women: The End of Patriarchy, Terran Williams makes this observation about the historical understanding of women, “. . . it was only recently that the church finally and formally began to widely and proudly embrace this equality as a matter of church doctrine.” He remarks that female inferiority recently joined other church-sanctioned “doctrines of men” in the ash heap of history — beliefs like a flat earth, geocentrism, and the legitimacy of racial slavery.1 Williams draws attention to the fact that the norm for all of human history until the latter half of the 20th century, both in secular society and inside the church, including the Reformed tradition, was the conviction that women were inferior to men. Half were regarded as “other” and that “other” meant “less than.”2

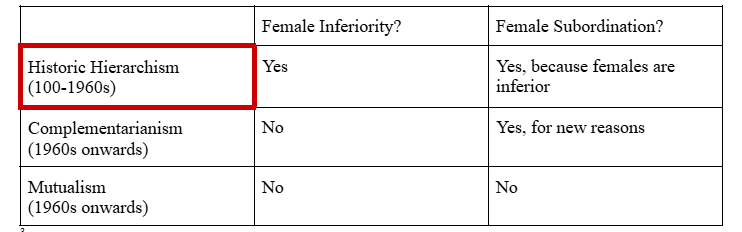

Can we stop and think about this as a church? Can we consider this blindness, this judgment passed against our neighbor, endorsed for millennia? The chart Williams provides is simple but stunning:

In contradiction to the second great commandment, to love my neighbor as myself, which entails esteeming her as myself, Williams suggests that we aligned with the world in demoting half of our neighbors. Generally speaking, historically, the visible church sided with culture, sanctioning the devaluing of half of us. I will suggest in this Substack that attributing this inferiority begins with rejecting the image as the stamp of God, the radically-equalizing, universal mark of our likeness to him. In believing and preaching the inferiority of half of us, we considered God and the work of his hands, lightly.

This pause to think is exactly what Terran Williams says the American Presbyterian, Reformed, and broadly evangelical church did not do in the 1960s. Instead, they rushed to put in place “new reasons” for subjection, a paradigm called “complementarianism,” based on “gender roles,” and, in the process, perhaps revealing what some considered most important.4 Many were finally willing to grant this abstract equality to women as long as there were no concrete changes in what Christian women did, because that would be a joining the “widespread uncertainty and confusion in our culture.”5 Instead of sitting in silence, grieving that we as the church had endorsed Aristotle with certainty for so long, getting something so monumentally important so completely wrong, the evangelical church quickly moved with certainty to create a new paradigm.

These are words of Wayne Grudem recounting that crucial moment at the 1986 Evangelical Theological Society (ETS) meeting in Atlanta:

(a group of us) talked over the situation, and we then met secretly one evening with several others . . . We all were saying that we had to do something because egalitarians were taking over the ETS. . . So I made an announcement at the end of the ETS meeting that if any others would want to join us in a new organization dedicated to upholding both equality and differences between men and women in marriage and the church, they should please talk to (us).6

What began with secret meetings and fear of take over developed into the Danvers Statement (1987) and the creation of the Council of Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, formed to promote the views of the Danvers Statement.

This is how Terran views that same time,

Then something happened in the US that I believe illegitimately brought the conversation to a premature end: The Danvers Statement, with its new teaching called “complementarianism,” was formulated.7

Williams clarifies again that up until the 1960s, the predominant teaching of the church was that women were functionally subordinated to men because God made them naturally inferior to men. The new teaching was that women were created equal but subordinated all the same.

Complementarianism was established primarily on interpretations of a handful of New Testament passages, some notoriously difficult — namely, 1 Corinthians 11:2-16 and 1 Timothy 2:11-15, and much was riding on the meaning of one Greek word, kephale (head), in Ephesians 5:23 and 1 Corinthians 11:3. This emphasis on kephale in 1 Corinthians 11 brought the movement to introduce hierarchy into the trinity as the model of male authority and female subjection. In 1985, Wayne Grudem began to write on kephale. He set out to prove that, used metaphorically, kephale always means “functional superior,” something akin to “ruler.” He wrote as if the complementarian movement depended on it. In the end, his work on kephale spanned decades and included articles and book chapters, especially as he responded to those who found misrepresentations in his writings.8

At the heart of the complementarian movement and CBMW is an understanding of gender “roles,” a word found six times in the Danvers Statement. A decade before the Danvers Statement, Covenant Seminary’s George Knight drew attention to the term in his book, Role Relationships of Men and Women: New Testament Teaching (1977).9 The title reflects honestly the fact that “role relationships” are not central to the Old Testament. “Vocational homemaking,” a phrase used in the Danvers Statement, is not commanded in the Mosaic law. It is not even remotely central in the Prophets or Writings. In fact, the Old Testament seems almost completely ambivalent about what Knight wants to center with regard to our differences as male and female, with potential impact on the daily lives of every one of us.

Terran explains that the church sanctioned a misrepresentation concerning women for two millennia, which evidently took less than 20 years to sort out and also apply. Those “roles” are “motherhood, vocational homemaking, and the many ministries historically performed by women.” As a personal side note, if I could roll back time and do it all over again, granted the same opportunities, I believe I would have chosen to serve my husband and children, and yet done it with greater freedom and joy, not under the burden of conforming to “gender roles.” Serving my husband, and the children God gave us, would have fallen under what God says is like the “greatest commandment,” loving my neighbor as myself, as our marriage reflected the mystery of Ephesians 5:31-32. By the way, mirroring that mystery explicitly involves the husband living out precisely this — to love his neighbor as himself (v. 33).

I suggest that Ephesians 5:18-33 does give us something that we might call “gender roles.” It gives us a paradigm for marriage, but that paradigm is not male authority and female submission, which distorts the mystery being revealed. Ephesians 5 gives us a pattern for life in the self-denying love of Christ. Love is the theme of Ephesians — the love of God in Christ, who is uniting all things in himself, things in heaven and things on earth, who accomplished redemption and now reigns as head over everything for the sake of his church (Eph 1:1-2:10). His power is at work toward us and for us. The union of everything in Christ —God and man (1:3-8) and things in heaven and things on earth — is not only our end as redeemed (1:9-10) but the hallmark of his church (Eph 2:11-4:16) and on display in our interpersonal relationships (4:17-6:9). Our Divine Warrior has defeated his and our enemies, clothing us with his righteousness, to this very end — that we might proclaim the mystery first announced in Ephesians 1:9-10, all things brought together in Christ (6:10-20; cf. Is 58). In all these things, Paul is emphasizing that we are participating in something huge, something cosmic, something encompassing the realm of angels and the realm of men, things too marvelous for us, things immeasurable, things we do not yet fully understand, “mystery,” mentioned six times in Ephesians, more than any other letter of Paul. That is what we should be grappling with in Ephesians 5, not how to extract a model for male “authority” from that passage.

I was born in the 1960s, as the church began to ascribe equal dignity to women, but my marriage coincided with the Presbyterian and Reformed-led response to the fear and uncertainty egalitarianism evoked and the origins and influence of the Council of Biblical Manhood and Womanhood.10 As I look back, I came to believe that being created second in Genesis 2 meant women’s subservience and that their sin in Genesis 3 made their opinions suspect. You notice that I say “their,” because for much of that time, I do not think that I placed “me” in that “them.” It was easier to devalue that group of people out there, “women,” than myself. But in the end, after a decade of our family following Doug Wilson, I began to internalize my inferiority.

We may try, but we cannot separate essence from “roles.” If half of humanity has its origin and purpose rooted in God, and the other half has its origin and purpose rooted in (mere) man, as many complementarians teach, that involves dignity. We cannot circumvent it with new terminology, new ways of talking about it.

The complementarian system calls women to fall in line with the “role” assigned to them at birth. According to the Council of Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, they are that half of humanity who evidence maturity by “affirming, receiving, and nurturing” the strength of that other half of humanity. Although complementarians deny this is “essential,” women’s marching orders are indisputable from embryo stage and continue until death, although some might argue they go forward in the age to come.11 There might be some choices along the way, such as whose strength is affirmed, received, and nurtured, as long as that strengthened neighbor is not a woman.

Trying to live out patriarchal complementarianism disoriented me. I was making my best effort to believe something that, perhaps, at some invisible, unfathomable depth, was antithetical to me. Some might ascribe that internal struggle to my personal sin, pride, or the supposed “curse” of Genesis 3:16.12 I believe that my struggle did not stem from anything “contrary to my husband,” but rather from something “for me,” something true about myself — something true from God about me before my husband came into my life and that will endure for the long ages that lie ahead of me, after the shadow of earthly marriage has given way to substance in eternity. I have come to believe that not only does the vestige of a knowledge of God remain with us after the fall, but also the vestige of a knowledge of self and neighbor as “from him and through him and to him.” Perhaps we can never shake completely free of the sensus divinitatis (sense of the divine) or the sensus humanitatis (sense of the human).

As I have mentioned before, the Presbyterian and Reformed tradition may have joined the post World War II consensus of those who acknowledge the equality of women, but they have concentrated little effort magnifying it, much less fortifying an exegetical and redemptive-historical account of it. In fact, I would say that the bulk of their endeavors since the 1960s tell us what a woman is not, not what she is. It is perhaps too self-evident for most Reformed and Presbyterian scholars to assert that the woman could not possibly be an image of the Father, the patriarch of Trinity. Doug Wilson will assert that anyway.13 According to Wilson, woman is not only not an image of the Father, she is antithetical to the Father, who is the archetype and wellspring of masculinity and authority. The Presbyterian tradition, however, does draw attention to males as an image of the Son, especially in its theological rationale for the “special office.”14 The tradition finds the woman antithetical to the Son, the Mediator, especially as he fulfills his three offices. Adam stands in contrast to Eve as firstborn and son, functioning as the prophet, priest, and king of Eden.15 Finally, they will assert that Eve is not an image of the Spirit. In fact, according to Reformed scholar Meredith Kline, the Spirit fathered the first Adam and the second Adam as sons, the two Adams created as the image and glory of the Spirit. Kline calls this the “prophetic and priestly model of the image of God.”16 Males alone can be the glory- image of the Spirit because Adam alone is underived, directly from God. Eve may be in a general sense the “creational image” of God, but her derivation from Adama means that she is the image and glory of the creature, not the Creator. Her image is one of being derived from Adam, signifying that she is Adam’s son and, as such, under his authority. Kline writes in a footnote,

Whenever the man (husband)-woman (wife) relationship is used in the Bible as a figure of a divine relationship, that relationship is always one between God and man.17

For Kline, the difference between the image of the male and the image of the female in Scripture is quintessentially antithetical, mirroring the first and last, the immutable and enduring antithesis — the Creator and the creature. The man represents the King eternal, immortal, invisible, the only God, to whom be honor and glory for ever and ever . . . and the woman does not.

Even though I believe that woman is indeed an image of the Glory-Spirit, it is not denying woman as an image of the Spirit that troubles me most. Nor is it evoking the fatherhood of God as a masculine image to distance me from God, as if that makes a case for my subordination. Rather, it is using Christ and his three offices to demote me. For over a decade, I have been listening and learning from a podcast put out by a Reformed organization. What they love to talk about most, and what I love to listen to most, are the episodes focused on biblical theology, the work of Geerhardus Vos and Meredith Kline, and those building on them. It took about six years before it struck me that women were all but absent from the discussion. In the hundreds of episodes and interviews that I listened to, next to no women discuss biblical theology. I assumed that they found no women whom they deemed competent to participate at their level, but after more listening, I also began to wonder if perhaps Christ’s maleness played a role. Perhaps in their eyes, women are not only excluded from the “special office” because Christ the Mediator is male, but his prophetic office prohibits mutuality and collaboration generally.

What would be my response to that? I not only acknowledge, but worship the enfleshed Son as the revealed center of redemptive history. The Old Testament foreshadows and heralds him, the Gospels reveal him, and the Epistles expound and apply his work as Second Adam. Christ is the focus and culmination of this present age in the Scriptures. And yet Vos gives us two ages, not only this age but the “age to come.” Is the Mediator the center of the coming age? Is he the center of the worship in heaven, the “upper register”? In Revelation, angels and men worship the one seated on the throne (Father and Son) in the Spirit temple. In Isaiah, Yahweh, one God, three persons, is worshipped by the angels as thrice holy. The Son is the absolute center of our history as redeemed mankind in this age, but could we say with confidence that he is the absolute center of Vos’s “coming ages”? Would we not rather say that the triune God, in whose image we are made before the fall of mankind into sin, must be the only and enduring center? In centering the maleness of the man Jesus Christ, have we forgotten “to the ages of ages,” εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας τῶν αἰώνων? Finally, could it be that by magnifying maleness, we may be marginalizing those “ages of ages,” mentioned 19 times in our New Testaments?

As I return to Terran Williams and his assessment of the church’s incredible change of course in the last 60 years, from advancing the inequality of woman to acknowledging the equality of woman, I mention that marginalizing that shift is not the only response. Many say something like, “Oh, of course, essential equality is what was always believed.” The record shows otherwise.18 Besides denial, the other way it is handled sounds like, “God is not really interested in this word ‘equality.’” Consider this quote,

Almost all assessments of gender seem compelled to begin with the assumption that no matter what we might conclude on A, B, and C, at the very least we all agree we must protect this general and abstract equality of male and female, while the biblical world suggests otherwise. In fact, what the world of the Scriptures says about male and female and its various spheres of relation suggests that we should not [emphasis added] grant that assumption at the outset.19

While I grant that author is concerned with equality, his statement that the “biblical world” is not, is striking. It implies that equality cannot be deduced from the image of God in mankind, which we find at the precise moment God is creating mankind in Genesis 1. I believe that this is what much of the Reformed world believes — that “image” says something about all mankind, but that something does not necessarily entail equality. Yet, even George Knight, for all his emphasis on essential gender roles, which he roots in eternal functional trinitarian relations, would not agree. He repeatedly states that the imago Dei is the heart of human equality.20

As I have mentioned before, there is a deafening silence when it comes to the Reformed understanding of the foundations of gender. Vos and Cornelius Van Til did not attempt to get to the root of our differences as male and female. When Hermann Bavinck and Meredith Kline took a shot at it, I humbly suggest they fail to make progress.21 It was during the so-called “Trinity Debate” of 2016 that it became clear to me that the Reformed had not discovered a sure foundation for gender. At that time, the consensus among that tradition was that it was not three hierarchically-ordered divine Persons, even though that teaching came squarely from their seminaries forty years prior and was disseminated by them.22 They agreed on what the foundation of gender was not, but they have made little progress since that time on what it is.

Despite not being considered an image of Father, Son, or Spirit, nor of Christ the Mediator in his three offices I would like to suggest a starting point — the imago Dei. It is where God starts. The starting point for understanding our diversity is understanding our unity, the image of God. There is something good within us that fights against devaluing ourselves. I see this in my friends from Central Asia. Some have left their native countries and now live in the United States. They come from places where laws all but vanish women, denying them education and restricting their movement in public. And yet, those women raised in such environments believe that they are equal to men, possessing a dignity commensurate to men. One told me recently that she can make a theological case for it from her holy book and the Hadith. I would trace that extraordinary impulse in my friend to the image of God.

As I understand it, in making us, he engraved his image upon us, endowing us with our common, irreducible essence as mankind. We cannot ignore God’s starting point in Genesis 1 in revealing to us who we are. The irreducible image is where God begins our first lesson in anthropology. We are his living icon, implying not only that we are related to him organically but also one another. When I say “irreducible,” I mean that we cannot parse the image as the Reformed have done. Dividing the image into parts degrades the image. When we attach the image to accidents, things about ourselves that could be otherwise, such as intelligence, will, ethnicity, nationality, gender, age, creativity, physical strength, power, or authority, or any other accident, we risk taking away the humanity of our neighbor by degrees. God says we have it, both before (Gen 1:27) and after the fall (Gen 9:6), and he gives us the ethical implications of it, but God does not explain it. In other words, the only explicit way that we know what the image is, is by how God applies it to our behavior.

By the application of it in Genesis 9:6, I would suggest that the Genesis 1:27 image is the human essence. Like God's essence, the human essence is simple (not composed of parts) and it is one (its singularity). There is not a male image of God and a female image of God. I suggest that we bear the same image in the same sense and to the same degree. I believe this is at the heart of the great commandment, to love our neighbor as ourselves. For Adam and Eve, the simplicity and unity of the image implied (1) that Adam and Eve were bound to love God because he had given them his image; (2) that they were bound to love themselves, because God had given them his image; (3) that they were bound to love one another because God had given their neighbor in Eden the same divine impression; (4) that they were bound to love the tribes and tongues and nations from them who would fill the earth; (5) and finally, that those tribes and tongues and nations would similarly be bound by the same law of love, by virtue of the same ineffable image (Gen 9:6; Ex 20:13; Luke 10:27; Rom 13:9; Gal 5:14).

Nothing adds or detracts from the Genesis 1:27 image. The image means we do not murder our neighbor, and more than that, that we love our neighbor, as we love ourselves. This is how God applies the image in Genesis 9:6, which he further inscribes by his own hand in the Glory-Cloud on Mt. Sinai in Exodus 20:13, and repeats by the mouth of Christ in the Sermon on the Mount, Matthew 5:43-48. This is how we are called to be like our Father in heaven. We perfect love out of reverence for God, whose image dwells in our neighbor.

I suggest that when we divide the image into parts, we open the door to dehumanizing our neighbor, stripping him of his humanity by degrees. And, as we have seen throughout history, denying our neighbor the fullness of humanity is the path that leads to exploitation and murder. It has led us as the human race to rationalize things like racial slavery, genocide, infanticide, especially female infanticide, senicide, and the murder of people with physical and mental disabilities. It has even led some to do this in the name of Christ, as if knowing that our sins are forgiven, that we have been given eternal life by grace through faith in Christ, makes us more human and more worthy of life on this earth than our neighbor. Similarly, when we separate the Genesis 1 image of God into pink and blue, the tendency will be to marginalize our unity as one mankind. God forefronts this unity in Genesis 1. We are one adam before we are male and female. Separating the image lends itself to a foundational “othering,” which leads to rationalizing our distance or indifference to our neighbor.

As far as I understand, the simplicity and unity of the imago Dei is not the historical Reformed position. The Reformed tradition has been alert enough to recognize the importance of the doctrine of the image of God. Traditionally it has been tied to “knowledge, righteousness, and holiness” before the Fall, a distortion of those after the Fall, and a capacity or gradual restoration of them through the Spirit in those “remade in the image of Christ.” Calvin writes,

Accordingly, by this term (image) is denoted the integrity with which Adam was endued when his intellect was clear, his affections subordinated to reason, all his senses duly regulated, and when he truly ascribed all his excellence to the admirable gifts of his Maker.23

A century later the Westminster divines agreed with Calvin:

After God had made all other creatures, he created man, male and female, with reasonable and immortal souls, endued with knowledge, righteousness, and true holiness, after his own image (Westminster Confession of Faith 4.2).

Notice that the image for Calvin and the Westminster Divines has parts, “particular properties in which it consists . . . faculties of the soul.”24 In other words, the “image” is anything but irreducible. Calvin’s definition implies capacity after the fall and that every person will be thought to bear the image by degrees, by actualizing the capacity in conforming to “knowledge, righteousness, and true holiness.”

In chapter 15 of the Institutes, Calvin delineates the image, placing a heavy emphasis on the intellect or knowledge controlling the lower impulses of the soul. Calvin alternately terms the lower impulses the affections, appetites, or will. For Calvin, this is what distinguishes us from animals. 25 At the time Calvin wrote, the higher impulse of the soul, the intellect, was associated with males. Females were associated with the lower impulses, the appetites. This was both a gender paradigm and a rationale for male authority and female subjection. Calvin quotes Plato and Aristotle 30 times in his Institutes, several instances in chapter 15, and he makes no effort to refute the prevailing gender paradigm of his day, that of Thomas Aquinas’s Summa, Aristotle’s sex polarity.

To be clear, the scholastic understanding of woman was that she was misbegotten, a malformed male, deficient in her access to the soul’s rational faculties. She was degraded, and yet Calvin writes nothing about the Aristotelian view. He takes no polemical stance against the anthropology of the Roman schoolman. He has lengthy discussions with Roman Catholics on tradition, the sacraments, the doctrine of justification, and the nature of true authority, but consider his silence on this distortion of biblical anthropology. Calvin’s letters show that he has no problem finding words when he is provoked by other teachings of Rome that he believes lead to exploitation, abuses, and injustice, but he writes nothing in chapter 15 of his Institutes that would correct medival misunderstandings of women. He says nothing there to restore that disparaged half of his congregation, of Geneva, of the broader Reformed world, of the women that worship in the tradition today. His silence leaves us wondering whether he fully accepted the reigning gender paradigm of his day. At the very least, we are left with doubts concerning whether he recognized Aristotle’s gender paradigm as a fundamental violation of the law of love. On a brighter note, I believe Calvin does leave us with a lead to pursue when he references the “eschatological” nature of the soul.

It is this point, the image and its relation to eschatology, where I would like to pick up next Substack as I look at the Son and the City in Isaiah. I suggest that our differences are not inherent in the simple, singular image of God, the human essence, and the foundation of our unity. Instead, our distinctions are found in our maleness and females as they relate to the decree of God to give his Son a Vineyard (Is 5), to bring his people to the Lord of Hosts and the mountain of his presence. In our fallen state, our differences tell us that even though our lives here are like the grass of the field which withers and the flower which fades, we are not to be afraid. The enemies of God may shake their fists at the mountain of Daughter Zion, the hill of Jerusalem, but the Lord of Armies will chop off their branches with terrifying power (Is 10). The Branch of the Lord will cleanse the heart of Jerusalem, creating over her a cloud of smoke by day and a glowing flame of fire by night, and over all that glory a hovering canopy (Is 4). The prophet Isaiah takes us to the heart of our differences as male and female as he points us to the Son and City, our great reward as image-bearing co-heirs of the promises of God.

If I could alter John Piper’s statement, I would say, “At the heart of mature masculinity and femininity is a willingness to consider our differences in this age as pointing us to the triune God who loves us and the glory he has purposed for us in the age to come. It is a disposition to understand maleness and femaleness in light of the Son’s work in bringing us to himself and the glory that awaits us in the Spirit-city.

Thank you for reading along. Next Substack, I hope to develop the prophet Isaiah’s use of gendered images, which takes us farther in our understanding of the Old Testament’s foundational gender paradigm. The Old Testament scholar, John Schmitt, found our significance as male and female in the Scripture’s masculine Son and feminine City. This is what needs to be developed.

Terran Williams, How God Sees Women:The End of Patriarchy, 42-43.

The demotion of women is seen most starkly in Old School Presbyterianism in the South, in the tradition of Knox and Scottish Presbyterianism, seen in the writings of Charles Dabney. See Isaac Tuttle, “Slavery, Submission, and Separate Spheres: Robert Dabney and Charles Hodge on the Submission of Wives and Enslaved People” (Themolis, Volume 50 - Issue 1), accessed here: https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/themelios/article/slavery-submission-and-separate-spheres-robert-dabney-and-charles-hodge-on-the-submission-of-wives-and-enslaved-people/

Williams, How God Sees, 46.

Ibid., 47-48.

Taken from the opening lines of the Danvers Statement, which can be accessed here: https://cbmw.org/about/the-danvers-statement/

Wayne Grudem, “Personal Reflections on the History of CBMW and the State of the Gender Debate,” accessed here: https://cbmw.org/1970/01/01/personal-reflections-on-the-history-of-cbmw-and-the-state-of-the-gender-debate/.

Williams, How God Sees, 43.

For his 1985 work, see Grudem, "Does Κεφαλή ('Head') Mean 'Source or 'Authority Over' in Greek Literature? A Survey of 2,336 Examples,” accessible here: https://womeninthechurch.co.uk/wp-content/plugins/kephale_grudem-1985.pdf. For examples of chapters and articles disputing Grudem’s claims, see here and here.

Williams, How God Sees, 48. According to Williams, a turning point came in the 1980s, when Knight urged two “rising stars,” John Piper and Wayne Grudem, to “enter the fray.”

The movement began with two graduates of Westminster Theological Seminary, George W. Knight III and Wayne Grudem, and the Reformed theologian, John Piper. See “Personal Reflections on the History of CBMW and the State of the Gender Debate,” accessed here: https://cbmw.org/1970/01/01/personal-reflections-on-the-history-of-cbmw-and-the-state-of-the-gender-debate/.

Mark David Walton, “Relationships and Roles in the New Creation,” originally published in the Journal of Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (JBMW) 11:1 (Spring 2006), accessed here: https://www.galaxie.com/article/jbmw11-1-02.

See Susan T. Foh, “What is the Women’s Desire?” The Westminster Theological Journal 37 (1974/75), 376-83. It was accessed here: https://blogs.bible.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/foh-womansdesire-wtj.pdf.

Douglas Wilson, For Glory and a Covering: A Practical Theology of Marriage, 40-41.

This teaching is pervasive. I have written about it here. Just one example is Michael Morales, Who Shall Ascend the Mountain of the Lord?, 236.

Meredith Kline, “Creation in the Image of the Glory Spirit,” accessed here: https://meredithkline.com/klines-works/articles-and-essays/creation-in-the-image-of-the-glory-spirit/.

Kline, Images of the Spirit, 34.

I appreciate Williams taking the time to trace the understanding of women historically in How God Sees, Chapter 2, “The Inferior Sex.” Prudence Allen has meticulously traced the historical influence of Aristotle’s anthropology in her three volume series, The Concept of Woman.

Mark Garcia, Theological Anthropology Lecture 1.3, “The Modern Situation: Equality, Essentialism,” https://www.greystoneinstitute.org/shop/p/reformed-liturgics-tg3pl-ec8xd-fww2a-9ldne. Mark Garcia’s extended discussion in Lectures 1.3-4.2 involves a rejection of the “modern gender equality” developed in the 17th century by the Reformed Genevan philosopher, François Poulain de la Barre, for the “sexuate installation” of the 20th century Spanish philosopher Julian Marias. Garcia uses Marias as the foundation for developing a “levitical,” “liturgical,” and “eschatological” model of gender and personhood based on the woman’s body as a replica of Zion. Her body becomes an image, giving us “the needed clarity for commending both the stability and the dynamism of gender roles.” Garcia sees the woman’s “reproductive cycle” as central to her biblical identity. She can draw near to God only when she is "fecund in life . . . resplendent with the glory of her Lamb-priest.” In the end, her body keys us to her identity, and Leviticus brings us to a “stability of gender roles.” For Garcia, this will ultimately mean that in worship she falls in line with her type as the “liturgical responder” to the “angelic priest-minister,” through whom the Holy Spirit is at work “to bring the bride to the Son and glory.” Likewise in the home, the woman will be the radiant reflection of the glory of her “priest-king” husband.

George W. Knight, “The Role of Women in the Church,” accessed here: https://www.bible-researcher.com/knight1.html.

In Bavinck’s The Christian Family, chapter 7, he wrote,"The woman must wrestle continually against her deficiency in logic that is manifested both in rigid tenacity and incorrigible wilfulness, as well as fickleness that defies every form of argument," accessed here: https://hermanbavinck.org/2013/04/03/women-haters-and-women-worshipers/. For Bavinck’s mature view, see “Bavinck’s Views on Women” here: https://aimeebyrd.com/bavincks-views-on-women/

George Knight was a Westminster Theological Seminary graduate (BD/MDiv, ThM), professor at Covenant Seminary, Knox Seminary, and Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary. He was an Orthodox Presbyterian minister; and in 1989, Presbyterian and Reformed (P&R) reprinted his 1977 book as Role Relationships of Men and Women: New Testament Teaching. In 2016, the Reformed consensus sided against the teaching that they had forwarded for 40 years.

John Calvin, Institutes, accessed here: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/c/calvin/institutes/cache/institutes.pdf, 167.

Ibid., 168.

For Calvin, the image is not found in a person’s body, but in the soul, which is “nobler,” and consists of “everything in which the nature of man surpasses that of all other species of animals” (Institutes, 163, 167). Analyzing the soul, he divides it into the functions of intellect and the will. He writes,

Man excelled in these noble endowments in his primitive condition, when reason, intelligence, prudence, and Judgment, not only sufficed for the government of his earthly life, but also enabled him to rise up to God and eternal happiness. Thereafter choice was added to direct the appetites, and temper all the organic motions; the will being thus perfectly submissive to the authority of reason. In this upright state, man possessed freedom of will, by which, if he chose, he was able to obtain eternal life (Institutes, 172).

Anna, so much of what you say here resonates with me because it captures my lived experience - and surely this is true for many of of us who follow your substack.

What stood out to me in particular in this essay is when you say that your internal resistance to complementarianism/ traditionalism was not rooted in something contrary to your husband or to masculinity, but rather stemmed from an urgent insistence that something was true/untrue about yourself as an image-bearer of God. I have never thought to put it in such terms myself, but you are exactly right.

A personal anecdote that came to mind bears this out. Growing up in the 80s, my sisters and I went through a tape recorder phase. One silly episode when I was probably less than 6 years old was captured on tape and, since finding and listening to it again when we were teenagers, has served as source of endless amusement to all of us. Essentially, I was dividing up cookies among various sisters and dolls, and allotted myself 5 for no particular reason, but then noted that "women are soo-prior to men so that's worth another 5." While we all still laugh (and apply the rule whenever it applies!) a question that my family and I have pondered has been, why was that even a thought in my head at that age? Your observation that resistance to poor teaching on gender is a heart's cry for the human dignity we all deserve as image-bearers might be a reasonable guess as to why.

At the same time, this very issue has been the single hardest aspect of discussing the topic with men in my life - men who otherwise are caring, Christian brothers. It's as if they simply cannot see that such resistance (or even mere questioning) can possibly stem from anything other than rebellion against the way God made the sexes and decreed how we are to relate to each other.

What has your experience been in discussing these topics with the Christian men in your life? And, though theology probably isn't a topic most unbelievers are interested in, have you ever had opportunity to discuss any of these things with non-Christian men? If so, how would you characterize the difference on how such conversations went?

There is a serious theological problem with viewing women as inferior to men. Jesus was born of a woman and had no earthly father; yet he is the Son of Man, fully human and fully God. In denigrating women, the Church has run the constant risk of denigrating their Lord's humanity. Only by seeing both women and men both as human before seeing them in their reproductive functions, can Christ's humanity be fully seen.